Closing the loop on mental health

Closing the loop on mental health

Closing the loop on mental health

How high-bandwidth brain-computer interfaces could transform psychiatric treatment

By: Maryam M. Shanechi, Ph.D.

Mental health today represents an urgent global crisis, with nearly one in five US adults living with a mental disorder. Mental health conditions are now a leading cause of disability worldwide, costing trillions of dollars annually. Yet our treatments remain blunt instruments. For example, current therapies, whether medication or psychotherapy, fail approximately 20-30% of patients with major depressive disorder.

One way to improve mental health therapies and psychiatry is to go beyond trial-and-error based treatment approaches that lack objective measures of mental states. Indeed, the lack of frequent, objective feedback about a patient’s response to therapy may lead to significant delay in finding an effective treatment for them.

In my 2019 perspective published in Nature Neuroscience “Brain–Machine Interfaces from Motor to Mood”, I asked what were then open questions:

- Could we envision a world where closed-loop BCI systems decode mood states of a patient from brain activity in real time to provide objective feedback?

- Could the same engineering principles that enabled paralyzed individuals to control computer cursors and robotic limbs through closed-loop BCI systems, also one day help decode and regulate mood symptoms, forming a new class of BCIs for personalized therapies in neuropsychiatric disorders?

Six years later, that vision is coming closer to technical feasibility. Our work back in 2018 demonstrated the first evidence on the ability to decode mood state from human brain activity and identify its neurophysiological biomarkers (Sani et al, 2018). Later remarkable work from other groups also provided evidence for this ability to find neurophysiological biomarkers of affective states in humans across multiple clinical indications, for example in studies on treatment-resistant depression (Scangos et al., 2021; Alagapan et al., 2023), obsessive compulsive disorder (Provenza et al 2021, Nhoet al 2024), PTSD, chronic pain and eating disorders.

Collectively, these studies show how neural interfaces may be able to objectively track mental states in real time, replacing today’s reliance on subjective self-reports.

Despite much promise, to date these studies have relied largely on lower-channel count measures of brain activity. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) systems, for example, have thus far had a limited number of electrodes and target regions. Furthermore, intracranial decoding studies in humans to date have largely focused on electrocorticography (ECoG) and stereo-EEG (SEEG). Indeed, these studies have not had access to measurements of populations of individual neurons.

The motor BCI field has shown that these neuronal population recordings can typically provide higher decoding accuracy in BCIs for movement decoding. This raises a key question: Can we improve precision and accelerate progress by using high-bandwidth BCIs for mental disorders as well? Because we have not had the technology to record such data yet, it remains unknown whether the neural representations of mood and psychiatric symptoms benefit from the same spatial and temporal resolutions that have proven effective for movement decoding.

However, emerging BCI technologies are beginning to make it possible to systematically investigate these questions at a resolution that was previously inaccessible.

Decoding and modulating mental states

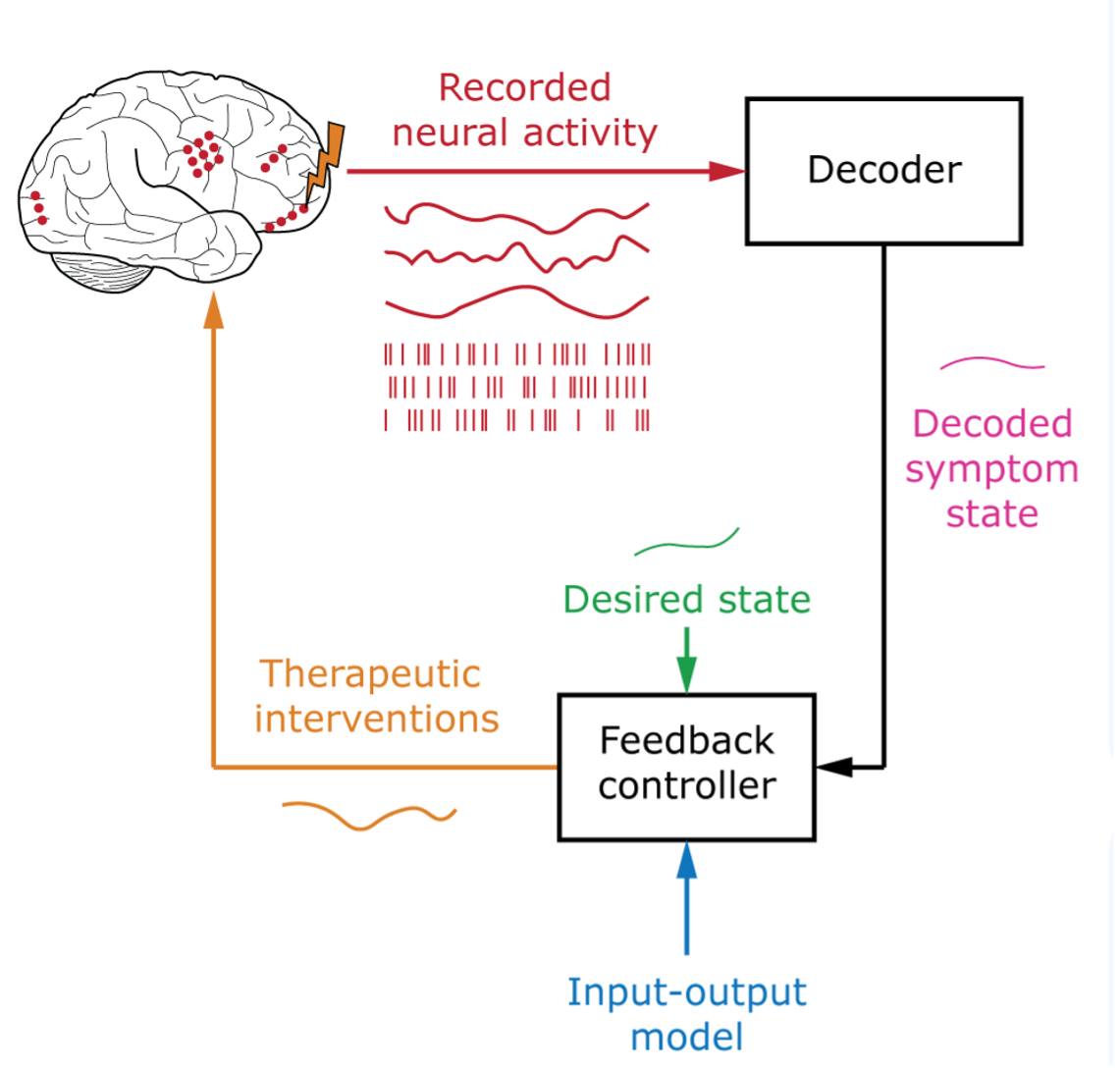

Realizing the ultimate vision of personalized, closed-loop treatments for mental disorders requires the ability to flexibly infer and modulate mental states mediated by the activity of distributed multiregional brain networks. Achieving such adaptive BCI systems rests on two essential components:

- a decoder capable of estimating latent mental states from brain activity in real time, and

- an input-output model that capture show therapeutic interventions, like electrical, optical, ultrasonic, magnetic, musical, or pharmacological interventions, affect these distributed brain dynamics and, in turn, their associated mental states.

Symptom states in mental disorders are the result of complex interactions between large populations of neurons across multiple brain regions. They can also exhibit inter-individual variability and evolve at different time scales. Given these spatial and temporal complexities in neural representations, it remains unknown what spatial or temporal resolution is ideal for decoding and modulating these symptom states and for guiding precisely targeted neuromodulation.

Distinguishing the variations in disease symptom states from those that are associated with natural variations in affective states, for example, can depend on subtle differences in spatial, temporal, and contextual patterns of brain activity. To date, most research on decoding or modulating affective states has relied on clinically available electrodes, like SEEG or ECoG arrays. In comparison, neuronal population recordings provide finer spatial and temporal resolution, but such measurements have thus far not been available for tracking mental states in humans.

We are at an important juncture in the BCI domain, where next-generation high-density intracortical implants may allow us to systematically address these key questions. These implants are capable of measuring and stimulating neural activity with millisecond temporal precision and neuronal spatial resolution. As such, these implants may help shine light on the temporal evolution, spatial patterns, and state-dependency of multiregional brain dynamics that underlie psychiatric symptoms.

They may also help us explore whether measuring the brain regions that mediate mental state at the level of neuronal populations can improve the precision by which we can objectively track how symptom states across diverse disorders changeover time. They may also allow us to assess the potential role of high-resolution, high-throughput neural data in treatments for mental disorders.

Over the past six years, my lab has developed machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) methods that enable flexible nonlinear inference of neural-behavioral states (Sani, et al., 2021; Abbaspourazad, et al., 2024; Vahidi, et al., 2024; Ahmadipour, et al., 2024; Sani, et al., 2024; Oganesian, et al., 2025) using both SEEG as well as high-resolution, multiscale intracortical neural recordings. We have also developed data-driven input–output modeling to predict brain network responses to electrical stimulation (Yang and Qiao, et al., 2021) in preclinical non-human primate research, using high-resolution, multiscale intracortical neural recordings and microstimulation.

These techniques have allowed us to build precise, predictive AI models of brain activity and its response to perturbation. These techniques can be used along with next-generation neural interfaces to discover the spatiotemporal neural patterns that underlie mental states and that can be modulated to regulate these states. Furthermore, in the future, these techniques have the potential to enable closed-loop systems for precise decoding and regulation of abnormal activity patterns in diverse mental disorders.

Looking forward

When we first proposed extending BCIs from motor to mood, it was an intellectual challenge - to imagine whether we can design AI-driven engineering systems that could capture something as complex as mood states. Today, we have more scientific evidence and are starting to turn our vision into a roadmap. Our advances in AI-driven frameworks can shape the development of future closed-loop systems for mental disorders - systems that sense, predict, and intervene in real time.

While in the past we have searched for the neural basis of mood using clinically available electrodes, next-generation BCI devices can enable measurements of brain activity across much broader spatial and temporal scales. We can thus begin to look for the neural underpinnings of mood and mental states with greater precision.

Six years ago, I wrote that the same engineering principles that restored movement in paralyzed patients might one day help us treat mental disorders. I am very hopeful that rapid scientific and technological progress will allow us to realize this vision.

Frequently asked questions

Could "high-resolution" neural data help decoding for something as slow-moving as mood?

There are two aspects to this question. First, regardless of the timescale over which mood symptoms evolve, decoding depends on having sufficient spatial resolution and signal quality to reliably capture relevant neural patterns. Our current work, and that of others, has demonstrated encouraging results using clinically available electrodes. At the same time, higher-resolution recordings provide an opportunity to investigate whether finer spatial detail and larger channel counts can improve the precision and reliability of decoding.

Second, although mood symptoms may appear slow-moving at the behavioral level, they likely reflect interactions among distributed neural populations operating across multiple spatial and temporal scales. This complexity can make it challenging to distinguish natural emotional variation from pathological symptom states. High-resolution interfaces offer fine-grained spatial and temporal measurements that may reveal additional structure in these distributed dynamics. Importantly, these emerging tools make it possible to systematically examine whether increased spatial or temporal resolution enhances our ability to track symptom states and guide personalized interventions that are responsive over time.

Does this require targeting deep, hard-to-reach areas of the brain?

There are two related questions here: where to target for stimulation, and where to sense activity for decoding and biomarker tracking. Historically, many deep brain stimulation studies have focused on subcortical structures for stimulation. However, there is growing evidence that meaningful information about internal states can be decoded from cortical activity as well. Increasingly, mental health conditions are understood to involve distributed networks spanning both cortical and subcortical regions, rather than being confined to a single anatomical location.

Motivated by this network perspective, we and others have developed AI-based modeling approaches that can integrate high-dimensional neural activity across regions and scales. At present, it remains an open scientific question which brain areas, and which combinations of sensing and stimulation sites, are optimal for decoding and modulating specific symptom states. In some cases, cortical sensing may provide meaningful information for tracking symptom states, while stimulation targets may reside in deeper circuits. These decisions will ultimately depend on careful clinical and scientific evaluation, which may be facilitated by new technologies.

How does this differ from existing treatments like medication or standard DBS?

Many current treatments, such as medications or traditional DBS, operate in an open-loop manner - meaning they deliver intervention according to pre-set parameters without continuously adjusting based on real-time measurements of the patient’s brain activity. A closed-loop approach, by contrast, incorporates ongoing neural feedback to adjust intervention dynamically based on measured changes in brain state. This feedback comes from decoding patterns of neural activity.

In this sense, a closed-loop system functions more like a thermostat that maintains a stable temperature by responding to changing conditions, rather than a heater that runs continuously regardless of need. By responding to shifts in brain dynamics, intervention can be tailored more precisely overtime to the individual and their evolving symptoms.

Is it possible to "decode" something as personal as a human emotion?

We aren't reading thoughts. Rather, we are identifying physiological patterns associated with clinically meaningful symptoms. Using AI to detect patterns in neural activity may allow clinicians to objectively track how a patient’s brain state changes over time and in response to therapy. This approach can enhance assessment by complementing subjective self-reports with continuous, objective brain measurements, helping guide treatment decisions in a more timely and data-driven manner.

%20(1).svg)